Poetic cinema is an ever elusive term that branches out into vast territory. Some associate it with the “arthouse”, others with the “avant garde”; two types of film making that in themselves escape lucid distinction.

Poetry itself is an overarching monstrosity of concepts and aesthetics, so what part of poetry does “Poetic” cinema refer to? The poetry of TS Elliot is different than that of Goethe or Breton or Whitman or Poe. It might be said that “Poetic” cinema refers to poetry, simply, in its difference to prose; prose equating a somewhat consistent temporal and spatial topography and poetry sacrificing this consistency and clarity in the favor of immediate experience and immersion.

The chaotic and elusive reverie of dreams and memory, then, are primal elements of vision that could provide that experience. Poetic film makers to an extent either delve into private dreams of their protagonists or fashion their whole aesthetic on the visual chaos of dream where rationale takes a backseat.

A sense of urgency also could be a formal element of the poetic; of immersing the spectator in a present moment either through a state of sedation or lingering on simple everyday scenes, where the film elevates itself from a series of events to a state of mind.

Basho, an Edo-period poet, claimed that Haiku (ancient and rigorous Japanese poetry) manifests itself to the observer when “you have plunged deep enough into the object to see something like a hidden glimmering…”. Poetic cinema is the chasm that gets us closer to that “glimmering” and replaces being with interbeing through distilling us into its images of immediate experience.

A cinema of poetry then could utilize the chaotic ether of dream/memory, forgo logical spatio-temporal consistency, record complex everyday human gestures or events or provide a sense of immersive visual urgency. With the term ”poetic” being still amorphous when applied as a criteria, the films on the list will construct a possible correlation, though ultimately condensed, of some films that inhabit one or all of the mentioned ideas.

1. The Mirror (1975, Andrei Tarkovsky)

In a dark melancholic timber cottage, a woman laments her husband’s absence while her children gather round a table pouring sugar over a cat’s head. The cat, unfazed, drinks spilled milk from a bowl of milk and cranberries that one of the children pensively tucks into. They are all lured outside, attracted to a barn engulfed in vivid fiery ember. The camera pans across awestruck subjects sandwiched between the alluring fire in the background and water dribbling from the cottage roof in the foreground.

It’s this richness of detail and visual poetry constantly evoking the ethereal and the supernatural that pours out of every orifice of Tarkovsky’s ode to memory and obsession. Archives of a violent war. A white dove flies over a levitating angelic figure. A dilapidated house, drowning in water, caves in on itself. These fragments of bliss are what grant The Mirror its elusive and transcendental quality.

2. Koridorius – The Corridor (1995, Sharunas Barthas)

The camera sways over faces in smothered awe peering out of windows and walking idly through a dilapidated apartment that resonates with quiet lullabies, haunting voices and pop songs. One of the younger tenants fires a rifle at a bird, downs liquor, and sets fire to a white sheet. A girl flirts frivolously with herself in the mirror.

Occasional inebriation seems to slightly curb the crowd’s ennui, as they dabble in idle chatter and flounder their lazy bodies about. The dawdling inhabitants are eternal dwellers of limbo, trudging through a corridor struck violently with latticed light. Their faces presume the form of some morbid nostalgia; a remembrance of ruined culture. The camera in the same way ponders over portraits of the dwellers with a weary and heavy gaze.

3. The Wind Will Carry Us (1999, Abbas Kiarostami)

A village, smothered in ochre, is etched into a rock. A film maker with a crew drives through the winding strokes of a wasteland decorated with dabs of tree-green. He arrives in the village and is caught in its primacy and ascetic habits.

The film maker is mistaken for an “engineer” by its inhabitants. He listens into a conversation between a tea shop owner and her old shabby husband. They argue about which one works the hardest. The “engineer” quietly and idly waits for an old woman to die so he can record an ancient post mortem ritual the village women perform.

The heavy hearted tenor of the woman’s fading is softened by episodes of a serene pregnant woman in her modest home. The austerity of the village is balanced with Kiarostami’s formal minimalism that issues from the spiritual.

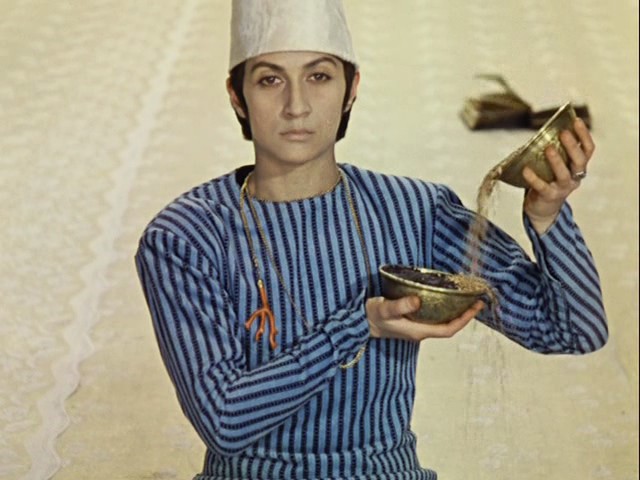

4. The Color of Pomegranates (1969, Sergei Parajanov)

Between ancient stoney ridges, a boy lies supine surrounded by open books, their pages flailing in the wind. The boy is aligned with their geometry. The young inquisitive gazes curiously at the work of dyers engulfed in steam. The wet hanks of wool, newly dyed, leak droplets of vivid red, pink and dark blue.

The boy later becomes a poet and priest of a monastery. He has a dream of stone-faced figures drowned in black; his father lays still, suspended in air while the priest imagines his younger self pendulating a silver orb with a decrepit angel with bony, featherless wings. His death is marked by the vision of a pale beauty covering him in blood-wine before being led to a barren field, his myth living on through angels frolicking with his musical instrument away from his frigid path.

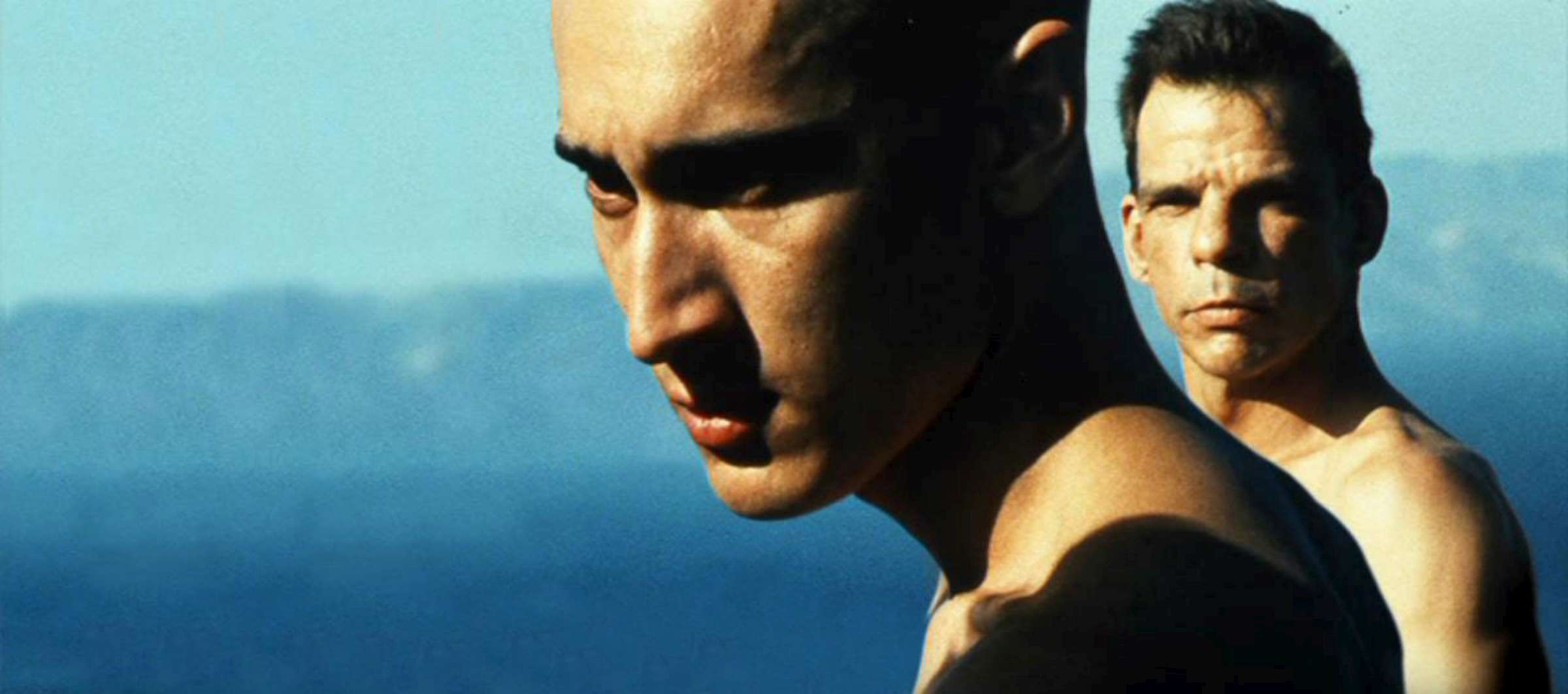

5. Post Tenebras Lux (2012, Carlos Reygadas)

Near-dusk, a wet mossy land with dabbles of water pools is over-arched by a violet sky. A small jubilant girl, as if suddenly bestowed with life and sight, curiously runs after a crowd of dogs that are chasing a cow herd then a horse drove. Cow-bells, heavy splashing water and the little girl’s chuckles fill the air.

The violent gloom of the sky clouds the innocent scene in mystery and foreboding. A glowing demon quietly invades a house carrying a toolbox and creepily tilts his body to gaze into one of the rooms. The two prologues are dreams of a family and auguries of their emotional exile.

6. Touki Bouki (1973, Djibril Diop Mambety)

A road movie about cultural estrangement, Touki Bouki constructs a barrage of poetic images and associations, combining both the everyday and the surreal. Mori and Anta, a pair of amorous Senegalese drifters, attempt a set of hoaxes and robberies to make fast money. The money would get them to Paris, in their minds an Elysium. The two seem spent up and travel calmly from one landscape to another. Mori sports a motorcycle decorated with cow skull-and-horns and a Malian Dogon cross.

The country’s savage culture is exposed when two men gash open the cervix of a goat. Mori and Anta drive in the baking wasteland with a repeated paean to Paris that sounds completely estranged from any reality compared against the image of scorched earth and bare-branched trees.

Around the world in 17 films: The Cinema of Childhood

Take a cinematic trip around the globe with our guide to the international gems screening in Mark Cousins’ The Cinema of Childhood season in cinemas and on the BFI Player.

Mark Cousins

The Cinema of Childhood season will launch 11 April at BFI Southbank, Edinburgh’s Filmhouse and other key venues across the UK. Funded by the BFI, the season will tour the UK for a year and includes 17 films from 12 countries, spanning seven decades. Eleven of the films will also be available to watch on the BFI Player later in April.

A Story of Children and Film is in cinemas nationwide, including BFI Southbank, from 4 April.

|

When we compiled our list of 10 great films about childhood last year, we limited ourselves to titles that were readily available for home viewing in the UK. This meant, regrettably, that some familiar classics were included at the expense of more obscure gems, but what’s the point in recommending something if it’s impossible to see?

A Story of Children and Film, Mark Cousins’ inspiring new documentary tracing representations of children in cinema from around the world, might have been one long recommendation for films that were impossible to see. A delight, sure, but also a frustration. Luckily, an accompanying season, The Cinema of Childhood, puts paid to all that. Seventeen films about children, from 12 different countries, will be screening at BFI Southbank and other venues across the UK, with 11 of the titles also available digitally on our video-on-demand service, the BFI Player, later in April.

With one fell swoop, the canon of classic children’s cinema is redrawn. We can now share in Cousins’ excitement about figures such as Iran’s Mohammad-Ali Talebi and discover for ourselves the magic in films that have until now been next-to-impossible to see.

To help you navigate your way through the programme, we’ve put together this guide to the 11 films available on the BFI Player, many of which have never been screened in the UK before.

Children in the Wind (1937)

Children in the Wind (1937)

Where’s it from?

Japan

What’s it about?

The idyllic village life of a Japanese boy falls apart when his father is falsely imprisoned.

Who made it?

A lesser-known (at least in the west) contemporary of Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu made some 160 features during the golden age of Japanese cinema, between the late 1920s and the 1950s. The recent release on American DVD of films such as Japanese Girls at the Harbour (1933), The Masseurs and a Woman (1938) and Ornamental Hairpin (1941) have made these his most familiar titles, but Children in the Wind is rare opportunity to experience an early example of the child-centred films for which Shimizu later became famous.

What Mark says

“Hiroshi Shimizu’s luminous masterpiece is nearly 80 years old, but still shines brightly.”

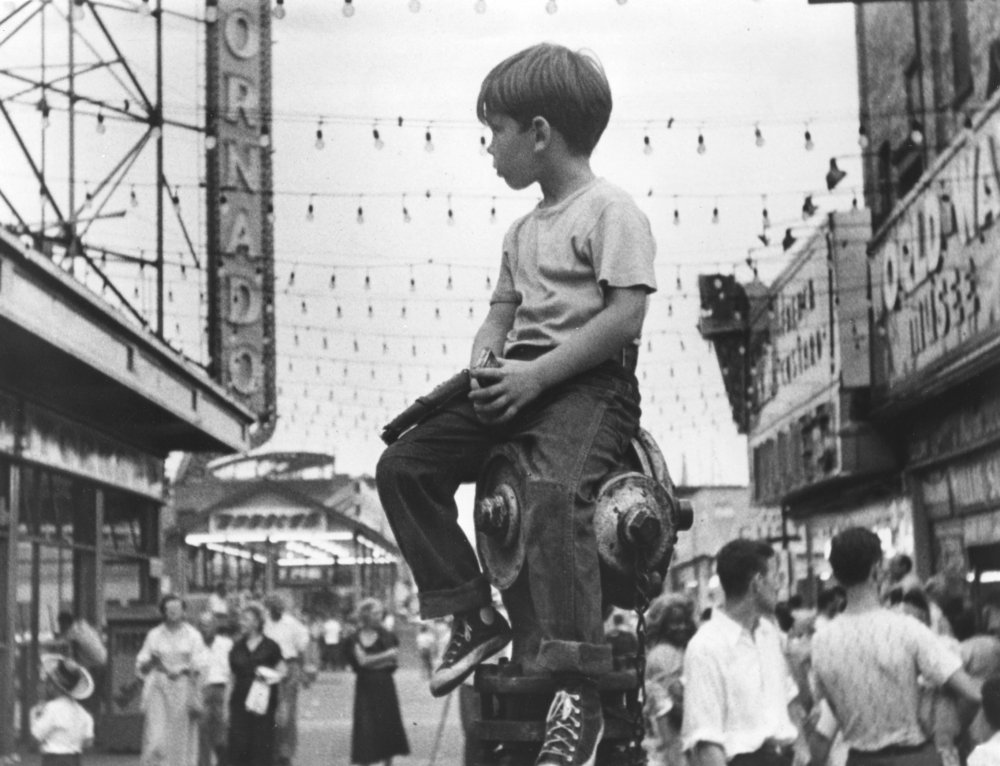

Little Fugitive (1953)

Little Fugitive (1953)

Where’s it from?

The US

What’s it about?

A seven-year-old boy runs away to Coney Island when he thinks he’s killed his older brother.

Who made it?

Brooklyner Morris Engel had been a combat photographer during the Second World War before returning to New York in peacetime. In 1953, in company with his wife Ruth Orkin and friend Ray Ashley (both fellow photographers), he picked up a hand-held 35mm film camera and took to the city streets and Coney Island to make Little Fugitive – among the first American films made independently from Hollywood.

What Mark says

“A film this fresh could not have been made in America in the 50s, and yet somehow it was – the first true indie movie, real life captured wild in the streets.”

Long Live the Republic (1965)

Long Live the Republic (1965)

Where’s it from?

Czechoslovakia

What’s it about?

A bullied boy tries to survive in a Czech village as the Germans retreat and the Russians advance.

Who made it?

One of the major directors of the new wave that reinvigorated Czech cinema during a brief spell of artistic freedom in the 1960s, Karel Kachyna is less familiar to the English-speaking world than contemporaries Milos Forman and Jirí Menzel. The banning of several of his films, including Long Live the Republic, until after the end of the communist regime ended in 1989 certainly played its part in keeping Kachyna’s work well below most cinephile radars.

What Mark says

“Beautifully shot and darkly ironic, Karel Kachyna’s forgotten masterpiece jumbles reality, memory and fantasy to capture the intensity and confusion of childhood in a war zone.”

Hugo & Josephine (1967)

Hugo and Josephine (1967)

Where’s it from?

Sweden

What’s it about?

The lonely daughter of a rural pastor makes friends with a wild boy who lives in the woods.

Who made it?

Once married to Bibi Andersson, one of Ingmar Bergman’s favourite actors, Kjell Grede has made only eight more features since making his debut with Hugo & Josephine in 1967 – none of which quite match the heights of his first film in the eyes of Swedish critics. But then Hugo & Josephine occupies a special place in their hearts: it’s routinely voted the greatest Swedish children’s film ever made.

What Mark says

“Kjell Grede delivers a Swedish summer classic, blond and gorgeous and heart-breakingly innocent. A pure pleasure.”

The Boot (1993)

The Boot (1993)

Where’s it from?

Iran

What’s it about?

A little girl craves a new pair of red wellies – but then loses one.

Who made it?

The Cinema of Childhood season is doing much to raise the profile of Mohammad-Ali Talebi, a one-time collaborator with Abbas Kiarostami who’s never enjoyed much attention in the west. The season includes no less than three films by the director, indicating just how important the pint-sized perspective in Talebi films like The Boot, Bag of Rice and Willow and Wind is to Cousins’ conception of children in the cinema.

What Mark says

“The story is fairy-tale simple, but the emotions swell, like in Bicycle Thieves. Director Mohammad-Ali Talebi had been working with children for years, and it shows. He makes Samaneh one of the most vivid characters in the movies. The Boot is a brilliant introduction to his world.”

Crows (1994)

Crows (1994)

Where’s it from?

Poland

What’s it about?

A neglected girl steals a younger girl and treats her as her surrogate daughter.

Who made it?

The daughter of documentary filmmaker Jadwiga Kedzierzawska, the director behind Crows is another talent who will be unfamiliar to most British viewers. Born in Lodz in 1957, Dorota made her feature debut with Devils, Devils in 1991. Both this and Crows, her second film, focus on young girls living on the margins of society. Talking about her 2011 film Tomorrow Will Be Better, she said: “As long as we have dreams, as long as we have faith, and as long as we keep hoping for the impossible, we find meaning in everything that surrounds us.”

What Mark says

“Dorota Kedzerawska’s remarkable film about a damaged girl trying to heal herself is tough yet tender, elevated by gorgeous cinematography and ultimately exhilarating.”

The White Balloon (1995)

The White Balloon (1995)

Where’s it from?

Iran

What’s it about?

A stubborn little girl wants a new goldfish, and won’t let anything get in her way.

Who made it?

Jafar Panahi is among the most famous of the directors with films in this season – though for unhappy reasons. In 2010 he was charged with creating propaganda against the Iranian government and issued with a jail sentence and a ban on making further films. The punishment met with international condemnation. Panahi’s work includes the riveting La Ronde-style drama The Circle (2000) and the exuberant Offside (2006), but he first assured his place among the world’s greatest living filmmakers with The White Balloon – a film which both the BFI and The Guardian have included in lists of essential family film viewing.

What Mark says

“Utterly real, quietly hilarious, totally brilliant. One of the most honest films ever made.”

The King of Masks (1997)

The King of Masks (1996)

Where’s it from?

China

What’s it about?

An old illusionist buys a young boy to become his apprentice – but the boy isn’t quite what he seems.

Who made it?

The late Wu Tianming, who died on 4 March 2014, was considered the godfather of Fifth Generation Chinese filmmakers such as Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige. As a producer and studio head, he helped foster their early careers – with his name appearing on the credits of some of the greatest Chinese films of the 1980s, from The Horse Thief (1986) to Red Sorghum (1987). As a director himself, Wu was best known for 1986’s The Old Well, the story of the quest for water in a poverty-stricken village, and this film, The King of Masks, made after a period of exile in the US.

What Mark says

“Swooping emotional drama about a kid who wants to be loved, and an old man who learns how to open his heart.”

Bag of Rice (1998)

Bag of Rice (1998)

Where’s it from?

Iran

What’s it about?

A little girl and an old blind lady decide to carry a sack of rice across Tehran.

Who made it?

Five years after The Boot, Mohammad-Ali Talebi made this follow-up of sorts, another tale of preteen determination and stubbornness.

What Mark says

“A gentle take on Planes, Trains and Automobiles, Talebi’s disarming film starts as an odd-couple adventure, then opens out into something profound and unforgettable.”

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1999)

The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1999)

Where’s it from?

Senegal

What’s it about?

A feisty disabled girl tries to improve her life by selling newspapers on the streets of Dakar.

Who made it?

Once seen never forgotten, Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty’s debut feature Touki-Bouki (1973) is the only African film to be voted into the top 100 of Sight & Sound’s once-a-decade poll to determine the greatest films ever made. Sadly, it was nearly two decades before he’d follow it up, with the similarly acclaimed Hyenas in 1992. He died aged 53 while completing The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun in 1999, which despite its diminutive 45-minute running time appeared on many newspapers’ best of the year top 10s. His body of work is small, but all of it is essential viewing.

What Mark says

“Djibril Diop Mambéty’s little film is a big-hearted odyssey about daring to imagine what you can be, and to hell with what anyone else thinks.”

Willow and Wind (2000)

Willow and Wind (2000)

Where’s it from?

Iran

What’s it about?

A boy breaks a school window, and must mend it himself before he’s allowed back in class.

Who made it?

Mohammad-Ali Talebi’s third film in the Cinema of Childhood season is his most recent, but as little known in the west as his others. As such, Willow and Wind is one of the season’s great recoveries, which (in a recent interview) Cousins told us was guaranteed to blow minds. In The Guardian, Peter Bradshaw writes: “it is utterly unreal, like a lucid dream, of such stark plainness that it seems like a quest fable from the middle ages.”

What Mark says

“In the hands of writer Abbas Kiarostami and director Mohammad-Ali Talebi, this simplest of stories becomes an epic quest, poetic and breathtakingly beautiful. It has big-hearted humanism, but Hitchcockian tension too. An edge-of-seat masterpiece.”

Also screening in cinemas

Palle Alone in the World (Astrid Henning-Jensen, Denmark, 1949)

A boy wakes up to find Copenhagen deserted, and it becomes his giant playground.

Forbidden Games (René Clément, France, 1952)

A boy and a girl retreat into a fantasy world to escape the horrors of the Second World War.

Ten Minutes Older (1978)

Tomka and His Friends (Xhanfise Keko, Albania, 1977)

A gang of Albanian boys in WW2 become secret agents for the Resistance when German troops occupy their village.

Ten Minutes Older (Herz Frank, Latvia, 1978)

One close-up, 10 minutes long, of a small boy’s face as he watches a thrilling puppet show.

Moving (Shinji Somai, Japan, 1993)

A girl struggles to come to terms with her parents’ divorce.

The Unseen (Miroslav Janek, Czech Republic, 1997)

Documentary about Czech blind kids with remarkable talents, including taking photos.

Read more: http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2015/20-great-poetic-films-that-are-worth-your-time/#ixzz4gTRJwc4j

you have picked some very good secondary research, but you MUST annotate your research to show your understanding

ReplyDelete